[REVIEW] Rune Factory 4 (3DS)

System: Nintendo 3DS

Release Date: October 1st, 2013 (NE), Q1 2014 (EU)

Developer: Neverland Co.

Publisher: XSEED Games (NA), Marvelous AQL (EU)

Author: Austin

There’s an implicit warning to the player the moment they start up Rune Factory 4, and it goes something like this:

“I really hope you like anime.”

Yes, the first thing you’ll lay eyes upon after clicking the game’s icon on the 3DS’ home menu is a fully animated music video where anime-styled characters are introduced and a Japanese woman sings a wonderfully cliché (in a good way, I might argue) tune in the background. If you had seen the video without any context, you may as well have assumed it was the theme song to a TV show or the title sequence of a film– and depending on who you are, that might be a joyous setting of stage for a game. Regardless, this opening is actually a very serviceable measuring stick for whether or not Rune Factory 4 will tickle your fancy.

Beyond that outer aesthetic layer, though, there’s a lot to Rune Factory 4: Players will be asked to tend crops, foster relationships (both romantic and platonic), tackle dungeons, learn to cook, forge items, take up chemistry– the list of activities, superficially, is extremely long. Quantity does not equate to quality though, and in the case of Rune Factory 4, the quality does prove somewhat unstable.

Unstable doesn’t mean universally bad, though, and much of what you’ll be tasked with doing in Rune Factory 4 is at the very least adequate at passing time. The core of your responsibilities in the game center around the fact that your player character– which can be male or female, by your choosing– has lost his or her memory and finds themselves in a foreign town (via a bit of a debacle on an airship; you were pushed off) full of folks who are ready and willing to befriend you and assist with your quest to figure out who you are and where you came from. That is, as a premise, all well and good.

And so, you begin to take up responsibilities– perhaps more aptly referred to as “chores”– in the town, which include things like farming vegetables and flowers, crafting items and weapons, romancing or befriending the townsfolk, and going out to fight monsters and conquer dungeons. The story conceits that surround these tasks are almost entirely arbitrary, and though they do provide some impetus to go out fighting instead of living a pleasant life of baking things for your (hopefully) future spouse, the game can’t be recommended on the face-value contents of its fairly pedestrian narrative alone.

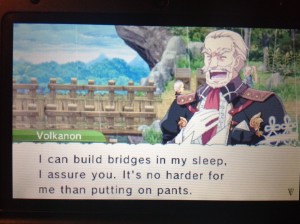

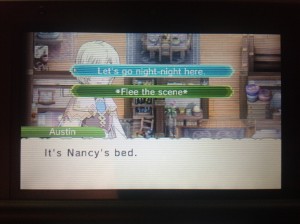

What it could be recommended on is its writing. The localization effort here is excellent, and XSEED did a superb job giving each character a distinct voice while managing to imbue the bits of dialogue with plenty of personality. Laugh-out-loud lines and more subtle, downright quirky bits of writing really give the game a strong sense of narrative voice; e.g. go up to another character’s bed, hit the ‘A’ button, and you’ll be presented with a choice:

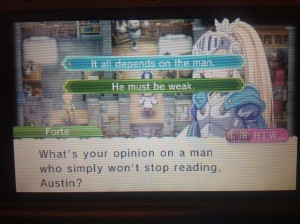

Talk to a particular character on a particular day, and they may present you with a question: “What’s your opinion on a man who simply won’t stop reading?”

These small conversational touches are central to what keeps the game interesting, and rarely do they feel done with anything but a light and elegant touch.

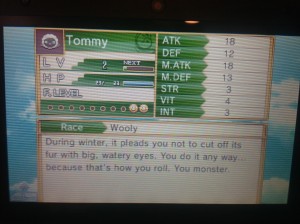

On top of that, these– perhaps you’d call them “trinkets”– of humor don’t limit themselves to the dialogue. Item descriptions will often have chuckle-worthy bits written into them, like the description of my pet sheep ‘Tommy’, which reads as follows:

Indeed, XSEED didn’t shy away from stepping out of the “comfortable translation” box in order to deliver something with a lot more heart than you might find elsewhere, and the game benefits greatly from that extra localization effort.

That personable, charming aim is coupled with the series’ staple marriage mechanic, which lets you pick from a variety of characters and try to impress them with cooking, gifts, or your combat skills in order to raise a heart meter and get them to marry you. This mechanic is both a blessing and a curse for Rune Factory 4.

On one hand, the ability to take a potential mate out with you on adventures into the game’s fields and dungeons to fight monsters serves the vision of the game very well. The interactions between you and someone you’re fighting alongside are personal, unique to your situation, and don’t feel canned or pre-determined by the game developers. The situations you may find yourself in with someone you’ve hopefully grown to care for are always subtly different, but it’s all the better for that– perhaps your significant other heals you at just the right moment to allow you to defeat a boss, or maybe you managed to beat down on an enemy who shot an arrow at your lover, enhancing the sense of satisfaction and strengthening your real-life feelings for this fictional character.

On the other hand, where cooperative combat succeeds, nearly every other method of seducing your potential mate ends up feeling by comparison disconnected and robotic. What might at one moment seem like a particularly organic and heartfelt connection gets turned into a machine of input and output– where the input is gifts and the output is a tick on the “heart meter”– where you’re periodically going to the store, buying food in a category that they’ve told you they enjoy, either cooking it or leaving it raw, and then delivering it to them. They have a similar canned response every time, you get the same things for them every time, and it appears to have an equally potent effect every time. These potential mates care not specifically what you get for them– only that such things satisfy a very obvious and rigid criteria so that enough “if” statements are met to give you a few points.

The problem here isn’t that this shallow method of input and output is inherently bad, just that there isn’t enough effort put into hiding the fact that it is and input and output method in order to trick the player into feeling something organic and genuine. Cooking food, buying gifts, or growing crops isn’t fun or challenging, and because of that there isn’t an ounce of satisfaction in doing it. The sense of satisfaction is supposed to come from the response that you get when you give someone a gift– and to a degree it certainly does– but the game asks you to do these repetitive tasks hundreds of times, which may end up putting a real strain on your patience for virtual love.

The one core aspect of the game that isn’t a time-sink is the combat, which is a much-needed addition to this Harvest Moon-inspired formula. While the rest of the game doesn’t come particularly close to challenging or stimulating the player (save for the writing), the combat at least takes a few small steps in that direction. It follows a typical button mashing hack-n-slash formula, but every so often an enemy will get your HP down to dangerous levels and you actually have to move strategically and find a safe place to take some potions (which is done in real time) before they kill you and send you home. This mechanic is certainly welcome amidst the tedium of the rest of the game, despite the fact that– standing on its own merits– it’s still two-dimensional at best, one-dimensional at worst.

These shallow game mechanics– gathering wood, planting seeds, harvesting crops, cooking, etc– aren’t by themselves the problem though. Plenty of exceptional video games have extremely shallow mechanics– perhaps most notably this year’s Animal Crossing: New Leaf— but to craft the highest quality game on a foundation of shallow mechanics requires a relentless attention to unique aesthetic detail. After all, if the game is fun and interesting to look at, listen to, and wander around in, doing monotonous tasks isn’t really such a big deal (for reference, see Animal Crossing: New Leaf again). Unfortunately, the game’s atmosphere steps not a foot outside of the safe-and-boring zone.

Character art in the game isn’t really artistically unique, backgrounds are flat 2D images overlaid with 3D models, “unimportant” sprites like logs and flowers manage to look entirely uninspired, and enemy designs are very generic, with a few minor exceptions. The only aspect of the game’s aesthetics that goes beyond middling is the music, which is– while not mind-bogglingly impressive– catchy, pleasant, and never dissonant with the rest of the package. Unfortunately that one element can’t save the game by itself.

This lack of trickery/polish is really the biggest problem with Rune Factory 4 on a grander scale as well. General tasks aren’t covered up by enough bells and whistles to hide their tedious nature, and they aren’t fundamentally developed in a way to translate a sense of innate satisfaction that would jive with the game’s obvious focus on organic and meaningful relationships and actions. It often gets close– and in those moments it’s easy to fall in love with the world and characters– but just as soon as you’re really starting to connect with what the developers have laid down, the wool is pulled back and you begin to see through the fundamentally shallow game mechanics, almost down to the numbers and algorithms that make it all possible.

Altogether, Rune Factory 4’s main failing comes as a consequence of its core concept: The game is designed to be a wide swath of extremely depthless activities that can eat up hours of your time should you so let it, and at that it succeeds to a moderate degree. Spreading its resources so thin, however, appears to have taken the game’s focus off of an attention to aesthetic polish, which would have been required to make something like this really shine. Perhaps it’s a bit of a developmental catch-22, but thankfully the game manages to avoid total mediocrity due to a fantastic localization effort.

Oh: or if you really like dating pretend animé people. And who among us doesn’t, at least a little bit?

Want to participate in more NintendoEverything goodness?

Try our Facebook page!

Or our Twitter page!