[Feature] Stop with the cat-suits and spin moves: The dramatic presentation of non-difficulty and how it relates to modern Mario

Austin note: This thing is not meant to be viewed as a criticism of a game that is not out yet (SM3DW) that I have only played twice before. It is also not meant to be a criticism solely of the Mario franchise. It is, as I hope is clear, a discussion and analysis of gameplay motifs and design philosophies for many kinds of games.

Kenta Motokura is co-director of the upcoming game-that-you’ve-all-heard-of, Super Mario 3D World. In a recent IGN article he said the following regarding the development of the game:

“Going off of our monitor tests, we wanted to see what beginners thought was difficult about the game, and also what was fun about the game. We learned from those tests is that if you were a beginning player, when you come to a cliff, you might stop, think about jumping, then jump and maybe not make it and drop. But what if we added this element of sticking to the wall so you could prevent yourself from dropping down?”

So he brings up this simple question: What if you added an element that prevented less experienced players from falling down?

It’s a simple question and one many developers have probably addressed subconsciously, but Motokura-san is reservedly letting us know that the folks over at EAD– in their expertise and design-mastery no doubt– are thinking not only about these questions, but also their implications and the implications of their answers. By now, we can assume such internal pondering has ceased because the team settled upon adding in a cat-suit power-up facilitating the traversal of vertical walls as discussed. The interesting question for me: What are the implications of this power-up?

Superficially (that is to say, if you examine the matter quickly and without too much thought) the cat-suit in Super Mario 3D World is a really clever and nifty design apparatus that organically introduces variable difficulty into a game. Players who’ve yet to master the physics or controls of Mario can still beat the game due to the design of power-ups, rather than due to the selection of an “artificial” difficulty option from a menu. This is good. Organic things are better than artificial things in pretty much every case.

But the introduction of such abilities– be it climbing up walls, spinning to retain altitude, or floating via water-powered jetpack– has the great potential to quietly suppress (normalize, moderate, dampen) an otherwise confident and expressive experience: It can, when used poorly, devalue the players’ actions and serve to make the whole experience feel less meaningful for those that attempt to truly engage with it. It is not a phenomena exclusive to Mario and a quick observation would reveal that non-Nintendo cases of this are much more extreme, though often less damaging to the whole of the work for reasons we may get into later. For the time being, I’ll give this phenomena the name “God of War disease”, though it didn’t originate with God of War nor is it exclusive to that series.

God of War, if you’ve never played, is a game that has your player avatar ‘Kratos’ (a stunningly angry and juvenile man, as it were) do a lot of things that look like they’re really impressive, even though what you’re actually doing as a player isn’t terribly impressive at all. Kratos leaps great distances, stabs some quite-large monsters in the throat, and kills creatures far more menacing-looking than himself; the player, conversely, merely hits a few buttons whose order matters only slightly at a pace that one wouldn’t exactly call “urgent”, much less “impressive”. Sure, if you were simply looking at it (and not playing it) you’d probably say something like “My goodness, that’s amazing! How are you doing that?”

But alas, such amazement is hollow, shallow, superficial, perfunctory, inane, inconsequential, superfluous, and illusionary. That last of those words is perhaps the most important.

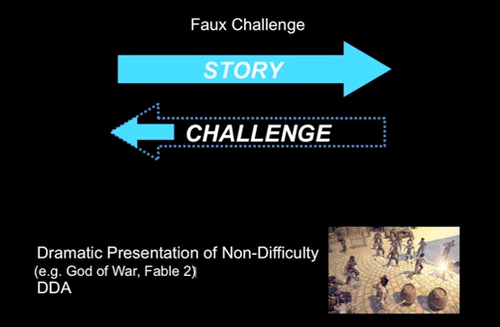

Jonathan Blow, in his 2008 talk about ‘Conflicts in Game Design’, explained this idea with the following diagram:

The larger outline represents the challenge they are attempting to convey to you (e.g. “You just killed a huge God! Good work!”), and the smaller filled-in arrow is how hard the action actually was. (he extrapolates to how this effects the traditional storytelling of a game, whereas I will not)

The phrase “dramatic presentation of non-difficulty” is a much more succinct way of explaining what I just took a really long time to explain.

——–

As I alluded to earlier, this problem is not limited to games like God of War, the aforementioned Fable, or Call of Duty, and it is, in at least two of those cases (I’ve not played Fable), less of an issue than it would be in something like Mario: Experiences like Call of Duty: Ghosts‘ single player campaign or God of War— unlike such games as Braid, Super Mario Bros., or Deus Ex— do not rely on satisfying gameplay in order to achieve a sense of greatness; their focus is on polished visuals and great sound design to convey a sense of awe, rather than direct, gratifying player interaction. (this is not to say that such games aren’t gratifying, though: they just get their gratification from elsewhere, and I may argue it’s a less gratifying gratification than when a game harnesses the power of gameplay)

So, what about Mario? Motokura presents this problem he and his team came across:

“if you were a beginning player, when you come to a cliff, you might stop, think about jumping, then jump and maybe not make it and drop”

While I would argue the validity of calling this a “problem”, let’s follow him down his line of thought: Beginning players can’t make it over some pit on their first try, and they, in the mind of Motokura and co., should be able to. The pit should not be something that you can fail at, and their solution to this is to add a cat-suit that lets you climb up walls and correct for your poor understanding of the in-game physics/reflexes/whatever. Now nobody, with any luck, will fall in the pit unless they really don’t know how to play!

Being the observant and curious people that we all most certainly are, we can’t help but ask the (loaded) question: In this new paradigm of cat-suits and other such corrective tools, why is the pit there, exactly? What purpose does a pit serve in this kind of game game?

Unfortunately, the answer isn’t terribly joyous: The purpose of the pit is no longer to be a challenge, but to create the illusion of a challenge. It’s Mario‘s version of the massive god that Kratos may take down in God of War, or the death-defying leap you make to a helicopter with one button-press in Call of Duty. The game is telling you that you did something impressive rather than actually letting you do something impressive. This is, to repeat: hollow, shallow, superficial, perfunctory, inane, inconsequential, superfluous, and illusionary. One may go so far as to say it is disrespectful to and patronizing of an engaged player. I would agree with that assessment.

These types of mechanics– things that, at face value, make something easier– aren’t always a hindrance to a gameplay-driven game’s vision though: It’s quite easy to imagine a game that uses a mechanic like this and incorporates it into the core design so it comes across as a flavor of gameplay rather than something inserted afterwards to help less-skilled players along– 2002’s Super Mario Sunshine is a prime example, but even better is 2007’s Portal. And on top of that, something like this existing isn’t actually entirely bad, even in the case of something like New Super Mario Bros. U. After I published the infant version of this article on my blog, someone commented via Twitter that the introduction of mechanics like this is the only reason why players of different skill-levels would be able to play together; the example he used was him and his father, if my memory serves. (Which it may not.)

So, should the focus of a game be on the local multiplayer experience (which isn’t conducive to being engaged and attentive anyway, due to the focus on real-life interactions with others), then these sorts of mechanics are completely excusable. It’s not always clear that Mario is about multiplayer though– particularly in the case of 2007’s Galaxy, but also in regard to the New Super Mario Bros. series on Wii and Wii U– so whether it’s totally excusable there is another matter.

Let me clarify though: Mario games are not devoid of merit of satisfying gameplay because of this phenomena. The games still do provide players with a challenge– a reason to be engaged– after the main quest is completed and more difficult, special missions open up; indeed, even the main quest often provides moments of difficulty– pits included– but it would be incorrect to conclude because of this that the level of engagement required from a player is not diminished by the inclusion of a fast-acting correctional device. You needn’t pay as close attention to what you’re doing when mistakes don’t have consequences, and adding to the problem (though it’s sort of a separate issue) is the fact that if you do manage to die in a modern Mario game there still isn’t much of a consequence. Perhaps things would be different if there were.

Such illusion has become a staple of many mass-market games these days– publishers (perhaps even developers) are scared that someone will think their game is too hard, get frustrated, quit, and never buy another game in that series. This is why the spin-move exists in New Super Mario Bros. and Super Mario Galaxy. It is why the phrase “games aren’t as hard as they used to be” gets thrown around a lot. It is why most games can be beaten by being disengaged (I call it “auto-piloting”) and ignorant of your in-game surroundings. You no longer need to pay attention and engage yourself because mistakes are correctable before consequences are laid upon ye.

The game expects nothing of the player, and gives much less of value to the player in return.