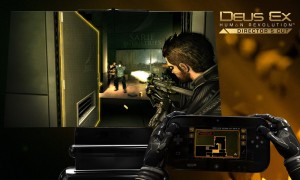

[REVIEW] Deus Ex: Human Revolution Director’s Cut

System: Nintendo Wii U

Release Date: October 22nd, 2013 (NA)

Developer: Eidos Montreal

Publisher: Square Enix

Author: Austin

Some games like to take themselves extremely seriously. Deus Ex: Human Revolution is one of those games.

The non-director’s cut (editor’s cut?) of this particular Eidos title came out back in 2011, and at the time it had not a home on a Nintendo console, which meant that folks who aligned themselves exclusively with the big N missed out on the game. When Square Enix saw the Wii U, apparently they also saw an opportunity to release an updated version of the game to a new audience– tag-lined “Director’s Cut”– and test the third party waters on this latest home console and its strange controller.

Roughly 7 months after the initial announcement, the game is out, and there’s good news: It’s pretty dang good.

At first glance, Human Revolution’s narrative comes across as heavy-handed, serious, and very unaware of itself. The game gives an extremely inelegant first impression, weighted with occasionally-laughably-serious dialogue and mediocre writing. It’s the sort of experience that will have you asking yourself if the creators knew how utterly silly most of what’s being said sounds; a Keanu-Reeves-inspired tone that– if taken seriously– could provide a bit of fun, but measured up against anything with genuine compositional value it would come across as seriously average.

The game follows the story of Adam Jensen, who– within the first hour of the game– gets beaten to the brink of death by terrorists (who also kill his girlfriend), only to be rescued by doctors that must replace a whole lot of his body with cybernetic enhancements known as “augmentations” if he is to survive. He is, effectively, the ‘Iron Man’ of the story: Once a regular Joe, now souped-up and ready to figure out who did this to him. It’s nothing you’ve never seen before.

The game tries to bring this mediocre (mediocre in its traditional meaning, “neither bad nor good”) story beyond its latent potential though by introducing a philosophical debate about what it means to be human. The world of Deus Ex (set primarily in Detroit, of all places) is divided into those folks who approve of “augmentations” (again: cybernetic enhancements to make you better at lifting things, seeing things, thinking, etc) and those who disapprove of them. Those in the latter group argue that we shouldn’t mess with the natural order of things; those in the former argue that we shouldn’t stop progress.

Effectively, this boils down to a mimicry of the real life forum on genetic tampering and stem cell research. It’s superfluous to the game’s good qualities, and would have been equally as ineffective (and less intrusive) had they pushed into the background instead of lacing most of the dialogue with a depthless analysis of a legitimately interesting ethical discussion. Some people may find the presentation of this debate moderately interesting (and indeed it is at least that), but the underlying moral “discussion” isn’t really anything terribly profound, and the designers don’t appear to be saying anything with it that scrapes beyond the superficial; they merely present an overly-simplified and black-and-white interpretation of the debate, and then ask the question “What do you think about all of this, player?”

To which you probably reply “Both sides are too extreme. Can I just play the game now?”

Step behind the narrative, however, and almost all you’ll find is very, very good. Let’s start by talking about the atmosphere and visual design.

While some may argue that, on a technical level, the visuals in Human Revolution aren’t anything to shake a stick at (and they’d be right), atmospherically the game hit its mark flawlessly. The environments are almost all made up of dark colors (black, grey, brown, etc) accented with yellow lights: Buildings glow with a slight golden leaning, outlines on usable items are yellow, and the fog that hangs around the skyscrapers of Detroit is tinted yellow as well– it looks just unique enough to stand out, and, combined with the classically cyberpunk model designs, the game feels very immersive and atmospherically sound. Of particular note are the occasions during which you can spend a few moments looking out a window at the distant skyscrapers of Detroit, such as from within Adam’s apartment. “Beautiful” may not be the perfect word to describe it; “haunting” may be more appropriate.

Sound design, unfortunately, isn’t quite as strong. Voice acting in particular can be especially weak, but the soundtrack isn’t necessarily notable either. It consists primarily of sustained chords and atmospheric sounds, which is par for the course if we’re talking about action games. Likely nothing you’ll remember after the credits roll, but it at least serves as a nice accent to the rest of the game’s aesthetic design.

But alas: what remains if you dig down to the core of what Deus Ex: Human Revolution Director’s Cut is? Is there really a well-designed game hidden beneath the aesthetic coveralls?

Oh yes.

Most of what you’ll spend your time doing in this game (when you’re not stuck watching cutscenes or trying to decipher the terribly complicated melodrama that plays out before you) is sneaking around enemy territory while moving towards a waypoint, and it’s a real testament to the game’s core quality that– even without an interesting story or tangible gameplay reward to propel you forward– it remains extremely fun and extremely satisfying to play. Utilizing the Wii U gamepad as a mini-map that tracks enemy movements (for which the extra screen real-estate helps greatly), you’ll be tasked with figuring out the best course of action in any given scenario by taking into account enemy movement patterns, the location of objectives, how much ammunition you have, what environmental things you could use, and what your goal is.

From the get-go the game tells you that it’s “up to you” how you want to play by letting you choose between a stealth weapon (tranquilizers and stun guns) or a deadly weapon (traditional rifles and pistols). Commendably, this choice is not a facade: Neither path is easier than its opposite, and ultimately the most effective method seems to be a very healthy combination of stealth and combat. If you attempt to go in guns-a-blazin’, you will die very quickly. If you attempt to avoid all confrontations with enemies, you will find that you cannot progress.

Alongside the game’s excellent damage/health parity, level design is particularly to blame for this excellent feeling of organicism and balance. Nothing seems strewn about by accident, and the designers clearly took a very healthy and intellectual approach to each location that you have to move through. Cover is sometimes placed helpfully, and other times it’s placed in a manner meant to break your momentum; the core thing about either of these scenarios is that they’re never linear. There are always multiple paths to take, but none of them– save for walking directly to your objective and crossing your fingers– are presented as obvious and contrived choices. If you want to take another path, you have to look around and find it yourself– the game doesn’t hold your hand through it.

And so it’s never a matter of having a singular path to take and then simply figuring out when to take that path– it’s always a matter of figuring out which path of many you want to take, and then figuring out when to take it. This extra layer turns a one dimensional game into a two dimensional one.

On top of all that, several other components manage to turn that two-dimensional design concept into a three or four dimensional one. The decision of whether to kill or merely subdue enemies is ever-present, and doing the latter will net your more experience points which will get you closer to your next augmentation (to be talked about later– sort of a “level up”). The downside? Subduing enemies (effectively just knocking them unconscious) means that if another bad guy stumbles across his sleeping friend, he can wake him up and they’ll both come searching for you. You have the ability to drag bodies around and hide them, but often times levels are designed to make that a fairly tricky endeavor, especially if there’s another enemy heading to your location on his patrol. And there probably is.

Another side to the game’s core gameplay (that makes… four dimensions I think?) is its simple use of environmental objects as tools for distraction or setting traps. Boxes and trash cans can be picked up and thrown to make noise, alarms can be activated to draw a group’s attention away from your location, security cameras can be commandeered to survey the land, and even the aforementioned unconscious/dead bodies are utilized for simple trap-setting. These items become your ammunition if your goal is stealth (and again, it will be at least some of the time), and the situations in which they’re used never feel pre-baked or contrived. It’s all extremely organic, varied, and up to your discretion how you want to use them.

Sitting atop even all of this intricacy and depth is yet another way in which you can choose how to play: Augmentations.

Effectively this game’s version of the “level up”, augmentations are things you can purchase for your character to give you special abilities. Some of these abilities aren’t particularly tangible– like the ability to hack higher level security systems, which are inherently contrived scenarios– but most of them are developed so that you get a usable gameplay reward. A super-jump, for instance, lets you get places that were previously inaccessible; a radar upgrade lets you see enemies on the bottom screen from a further distance away; a cloaking system lets you turn invisible for seconds at a time, which can be absolutely vital in certain situations. To make a useful comparison, these upgrades are the opposite of what has been seen in games like Zelda, where items feel more like glorified keys than anything. In Deux Ex, they feel like useful tools with many, non-contextual applications, even if they are, technically, contextual.

The one problem that arises from all of these choices, these augmentations, and these dimensions of gameplay is that often times– mostly in menus– the game feels overbearing and complicated rather than simplified and elegant. The inclusion of an atrociously designed, text-heavy tutorial system does the player no favors, and a menu system with too many similar-looking options, buttons, and symbols gives off the vague sense of looking at an airplane’s flight board, as though one couldn’t possibly make sense of it all without a thick manual. Even the touch-based navigation afforded by the Wii U gamepad cannot save it from over-complication.

Occasionally, when you’re not participating in the game’s wonderful core gameplay experience, other problems do arise, primarily because of that pesky thing called “ludonarrative dissonance” that many games suffer from. As an example:

I walked into the police station with the intent of gaining access to the morgue so that I could examine a dead body. Thankfully, a friend of mine was working the desk, so I talked to him (the game gives you the occasional conversational choice) and tried to get him to let me in. Unfortunately, he ended up furious with me over something melodramatic that had happened in our past and it was looking like he wasn’t going to let me in. Eventually I talked him into it, and went down to the morgue.

The morgue technician told me to do what I needed to do with the body, so I did: I removed the chip that I needed and triggered the next audio-cutscene (which play during gameplay) in which Adam (Jensen, the main character) and his allies back at HQ calmly discuss what to do next. During this brief respite, something happened and the entire police station began attacking me as though I had murdered one of their officers. I hadn’t done anything.

So I realized I couldn’t sneak past 30 policemen and went out the sewer access door, only to realize it was (what appeared to be) a dead end. I turned back around with the intent of fighting my way through the police station, since that appeared to be my only option.

Upon re-entering the building– which had been not five minutes prior on high-alert kill-Adam mode– none of the officers seemed to care about my existence. I walked out the front door– even talked to some of them on the way out– and they were none the wiser. I know not why they attacked me. I know not why the stopped attacking me. It was very strange.

Thankfully these moments are few and far between, but they do exist, and they are a detriment to the game’s goals.

There are also some minor control and camera issues that arise when you switch between first-person and third-person (first person for walking around, third person when you’re crouched behind cover), and the game sometimes feels like it’s begging to just be a third person game entirely– the fluidity of the camera in such a game would do the game a lot of good in the area of polish.

Fundamentally though, the game is very well developed and Eidos Montreal showcases a fantastic knowledge of gameplay design with what you’ll be doing for the bulk of your time in the dystopian world of Deus Ex. An admirable attention to atmosphere and visual design is the icing on the cake, and– though there are a few notable issues with ludonarrative dissonance (sorry, it’s a good phrase) and a few bouts of horrible voice acting/writing– what a tasty cake it is. The only major blemish appears to be the narrative, which is there only to impress the laymen with the illusion of depth and philosophy, even if such superficiality was unintentional.

Deus Ex: Human Revolution Director’s Cut is a game that almost anyone could get a lot of enjoyment out of. Carefully crafted levels, deep and organic gameplay, and a haunting atmosphere make it an experience that is not only superficially entertaining, but also intrinsically satisfying to play irrespective of any story conceits tied to it. Those with a distaste for overly complicated menus or upgrade systems may want to think twice before a purchase, but even then most of what there is to like will overpower such complaints for even the most hardened lovers of simplicity.

Avoid it if you absolutely cannot stand stealthy action. Avoid it if keannic/overblown stories really turn you off. Play it otherwise.

Want to participate in more NintendoEverything goodness?

Try our Facebook page!

Or our Twitter page!