[Review] Shovel Knight (Wii U eShop)

Update: Full transcript below!

Also available on 3DS! Austin takes on the newly released first-ever game from Yacht Club Games. Is it any good? Oh no, you’ll just have to watch the review to see. (Want to skip the analysis? Go to 10:51 for the recommendation on who should buy it and who shouldn’t)

I like shovels. I like the color blue. Put those things together and you get Shovel Knight.

Not really though. Let’s review shovel knight.

To pick up Shovel Knight is to pick up an adventure disguised as an arcade game. I’m not one for categorizations in many cases, but were you to try and label the first game from Yacht Club Games with a few simple words you’d probably fall somewhere near “organic platforming adventure”.

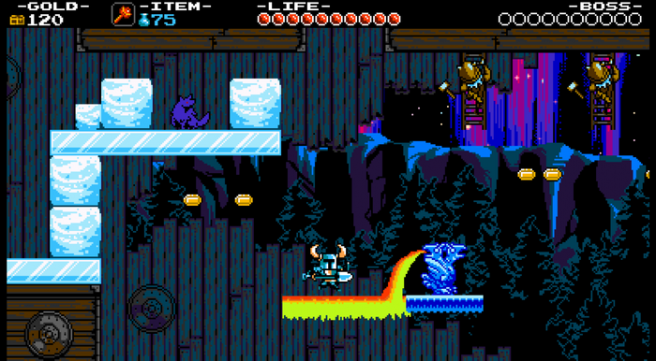

“Platforming” probably sounds a bit familiar. You look at the footage here and it’s clear that Shovel Knight’s core was derived from games like Mega Man and Ducktales– games we call “platformers”– with its jumping and shovel-smacking mechanics, its gems to collect and its sidescrolling level structure. Sure, Shovel Knight’s experience is certainly one seen through the lens of a platformer.

But what kind of platformer? “Organic” is the word for this. Some platformers– particularly as of late– have chosen to lean on a sort of rhythm-game sensibility. You’re given a clear set of actions to do– a clear set of buttons to press at clearly defined times– and beating the game is only a matter of executing that string of button presses with minimal mistakes. Mighty Switch Force! for one example. 1001 Spikes for another. These experience aren’t necessarily “organic” in gameplay– they’re a little more what we’d call “architected”.

Shovel Knight has a different philosophy. Though it brings in elements of those architected platformers, they’re used only in certain specific instances and rarely do they feel like puzzles with specific “solutions”. The game ends up being much more organic than that.

Organic meaning indeterminate. Most of the game is spent going through sections of platforming where it’s not defined from the get-go how everything is meant to play out, and the path you take depends on multiple factors like enemy programming or when in their attack cycle they are. This multi-path design is not done on a large and obvious scale, but rather a very very small, minute scale.

Take this section from one of the game’s early stages, the Lich Yard:

At the beginning of this ominous looking stage you’re presented with many more or less insignificant choices. We’ll mostly pay attention to the frogs coming up here, but make note of the fact that the gems you can gather are certainly optional. Ah yes, these frogs. The programming of these guys means they just jump towards you, and every so often they light up with electricity. Simple enough, right? But look at this scenario that has arisen: The game did not pre-determine that I would be assaulted by two frogs from behind and get shocked by this frog from below. That situation arose organically as the result of my actions and the programming of the frogs. That is what I mean by organic. It isn’t pre-determined how any given level will play out on a minute level.

Another great example is the beginning of Plague Knight’s stage, which does showcase one of the slightly more architected sections in the game. Though there’s clearly a “best” path here– it may, in fact, be the “only” path– the design of this section isn’t meant to evoke feelings of cleverness or intelligence. The impression this gives is not one of intricately crafted solvability that make you connect intellectually with the objective quality of the level design– it’s not supposed to feel like a game. It’s a place. It’s a level. You’re not traversing it in order to experience a gradual and impressive increase in design complexity– you’re doing it because you’re on an adventure.

And it’s this style of design that affords Shovel Knight the ability to feel like an adventure with a grander progression.

Other design elements that prop up this feeling of organicism are present as well, particularly the game’s decision to frustrate you or present you with enemies or situations that you simply don’t like dealing with from time to time. The hand of Shovel Knight is very selective in when and where these bits arise, but they do arise. One excellent example is within that The Lich Yard we discussed, Specter Knight’s home:

The game pulls out a classic 8bit move: Making everything go dark so you can’t see where you’re going. You can’t see where enemies are. You can’t even see where YOU are. The only sight you have is every 5 seconds when a flash of lightning crosses the screen.

This, as you can imagine, is not really “fun” in the classical definition of the word. It’s annoying. Having to wait five seconds in between every few movements, occasionally having an enemy jump in the dark and hit you without warning, or even missing a pit and falling in because it was too dark to see. These things are almost by definition unfair. Absolutely. And the game is better for it, because it is in these moments– if you’re not so daft as to write them off immediately– that you realize (likely subconsciously) that this is not a world built for you. This is a world built in spite of you.

Well, okay, literally technically on a development level it was built for you. Technically. But the design of the world is not one that panders to ensure a certain level of smoothness at all times– it exists, for all intents and purposes, for no reason other than that it does. The fact that you’re there is merely incidental. You’re not here to play a game– you’re here to take down some castles and beat some evil knights.

It is in this sense that the game becomes analogous to the adventures of reality– sometimes things go smoothly, and sometimes they do not, and it is with this tool that Shovel Knight digs further into a sense of coherence and adventure.

One of the ways the game makes these vaguely annoying bearable is through the aesthetic design– the visuals and sound.

In one sense the aesthetics– the visuals in particular– are used to accent a sense of progression and large-scale movement. When you go to three places that all look drastically different, it feels like you’ve covered much more ground than if you go to three places that all look the same. Simple human psychology, really, and the game takes tremendous advantage of that. You start out in a simple looking grass-and-dirt level, progress to a golden and purple castle, and then into a neon red, purple, and black graveyard. Later on you may find yourself in psychedelic laboratories or on top of a beautiful mountains. Expounding upon this sense of movement are the boss designs, which are all tremendously creative visually and sufficiently varied in gameplay; certainly, this strong and focused visual distinction from level to level helps support that feeling that you’re really trekking far and accomplishing a lot.

In another way, the aesthetics are used– as is customary in many games, really– to help soften the sharp edges of boredom or frustration that come up in the aforementioned areas of that are not “fun” outright, but play a vital role in the bigger picture. The token underwater level– not anymore pleasurable here than it was in Mega Man 2 or Super Mario Bros.– is made dramatically easier to swallow when you have mesmerizing visuals or jaw-droppingly catchy music to engage with. You end up with the adventurous benefits of frustration, but it leaves you less directly upset as it otherwise might.

The music should really be mentioned separately as well. It is perhaps even more vital in softening those frustrations than the visuals, but let’s first take a listen to a sampling so you can have an idea of what we’re in for here:

The strong melodies interplay with intricate support instruments in ways that remain catchy, but interesting enough so as not to get too boring very quickly. The way they function in gameplay is straightforward: When your frustration or impatience gets too high and your attention decides to leave the party, the music grabs it, slaps it across the face and pushes it right back into the room. And the room, it just so happens, is gorgeous because of the game’s visual design. It’s wonderful when multiple game elements work together, isn’t it?

The structure of the game is also laid out on a world map with various interconnecting points, some of which have stuff for you to do and some of which do not. Some of them have towns full of citizens with things to say and sell, some of them have wandering vagabonds who challenge you to duels on a moment’s notice. If your goal is to create a game with a strong sense of motion and adventure, providing a sense of place with a simple map certainly seems like a decent way to do it.

Did I say there were towns with things to buy? Oh yes, I did. You collect treasure on your adventures and that treasure can be used to purchase certain upgrades or weapons from shops or weird traveling merchants, and those weapons or upgrades can help you on your quest.

Allowing you to purchase things to increase your strength and abilities fits with the narrative of “progression”; when you get towards the end of the game with maxed out health and a slew of fancy weapons to play with, you certainly feel like you’ve come a long way from when you started. And those fancy weapons sure feel useful at times when things get tough, but we’ll keep them a secret so as to not spoil the surprise.

The other utility of this map structure with these towns and wandering vagabond’s is that the game now has a facility to lightly remind you that there IS a world here– the various encounters you have on your travels that aren’t related to boss knights will begin with brief conversations between Shovel Knight and his attackers or those in the towns. These conversations make passing reference to places in the world or events that have taken place, but the point is not for you to understand exactly what’s being said all of the time– the point is that stuff is being said about the world. This is, again, a world created not for you to consume, but a world created in spite of the presence of you as a video game player.

Narrative elements like this remain as light as they should given their relative simplicity, but the point is elsewhere: The game paints exactly the right amount of narrative coating over you to achieve the maximum benefit with the story that’s been written. Had any more storytelling been thrust upon you, frustrations would arise from your desire to simply “play the game”. Had any less storytelling been present, a portion of the adventurous effectiveness of Shovel Knight would have disappeared.

——————-

All of these elements thrown into the same box– the aesthetics, the music, the organic design, the overworld style, etc– do set the stage for a really tremendously well-oiled and tight adventure, but the final piece of the puzzle that will determine the game’s success or failure is its ability to pace itself. How well can it spread these elements around so as to evoke the right feelings at the right time?

With few exceptions, the game is really quite good at that as well. The general pace of the game is something like this:

You start out in a town– peaceful and stressless– then move onto a Knight’s stage. The stage is difficult, but with some perseverance you can make it through relatively quickly and end up at the boss encounter. Boss encounters are tough and intense, with the music and gameplay ramping up significantly, and they gradually intensify over the course of the entire game as well. Another way the game gives a sense of progression and over-arching movement.

After you defeat the boss, a triumphant fanfare plays and the game fades away to a peaceful scene of shovel knight resting by a campfire. You awaken him in the morning, put out the campfire (or don’t), and head off-screen to take the next step on your journey.

These campfire scenes are quite a hypnotic bit of non-gameplay because of how they diffuse the intensity of the boss fight that came immediately prior, and they are what help the game perform the tried-and-true adventure game dance of intensity and serenity. It not only feels intrinsically good to have a scene of rest after a tough fight, but it also helps further that sense of movement by putting off the impression of passing time. A smart move on the game’s part.

So Shovel Knight is a surprisingly adventurous game. It rests confidently behind the guise of being simple or purely gameplay-driven, but the organization and pacing of all its elements– the aesthetics in particular make a big difference– tell a larger story without getting in its own way. Confidence is perhaps the key word here: Shovel Knight is a confident game, enough so that it doesn’t feel the need to berate you with excess story elements, tutorials, or child-proofed level designs. It deals its cards with elegance, always knowing just how much emphasis to put on any given element such that none of them feel overdone or underbaked.

In short, it’s an exceptional game. And the music is so good.

The Recommendation:

Fans of platformers– particularly the premier platformers of the NES era– should not waste another moment before picking up Shovel Knight. Strong aesthetics make the experience memorable and tough gameplay means you’re consistently engaged with it, but on the flip side those with a distaste for dexterity-focused games may want to stay away, as Shovel Knight will certainly require a bit of quick-thinking and nimble fingers to get all the way through. It’s hardly the most difficult game out there now, but it’s no walk in the park either.

Still, as long as you can at the very least deal with gameplay-driven experiences, it wouldn’t be hard to recommend Shovel Knight. It’s a nigh-flawless experience through and through.